Parents of some haemophiliac children were not prepared for the news their child was infected with HIV from infected blood products because they did not even known they had been tested, an inquiry has heard.

The Infected Blood Inquiry has been told 21 children became infected with HIV as a result of their treatment at the Royal Hospital for Sick Children (RHSC) at Yorkhill in Glasgow in the early 1980s.

Dr Anna Pettigrew, a clinical assistant in the haematology department at the RHSC from 1980-1989, said it was an “awful moment” when staff at the hospital discovered some of their patients were infected after stored samples were tested for the virus.

Dr Pettigrew said telling parents that their child had HIV was an awful experience: "We knew these mothers, we knew these children, we'd watched them growing up. It was very distressing to have to explain to parents that this had happened to their child." #InfectedBloodInquiry

— The Haemophilia Society Public Inquiry Team (@HaemoSocUK_PI) December 7, 2020

Asked how parents were told their child was infected, she said after she learned of the news in 1985 she would tell them if she saw them in the hospital or she and a colleague would inform them when they brought their child in for their next routine appointment.

Jenni Richards QC asked: “Does it follow they would have had no advance notice or preparation for the news that was going to be broken to them because they didn’t even know their child had been tested?”

Dr Pettigrew replied: “I think that’s fair, I think there was a high index of suspicion among them that their child was at risk of being infected but certainly they they would not have known that they were going to be told.”

She said it was generally mothers who were at the hospital on their own, with no support.

Dr Pettigrew said “with hindsight” it would have been better to work out a way to give the news to both parents at the same time.

Reflecting on telling parents the news, she said: “It was a very, very distressing experience because we knew these mothers, I knew these children, we had watched them growing up.

“It was a very distressing experience to have to explain to the parents that this had happened to their child.

“It was an awful time.”

She said she had thought about it many times over the years, adding: “I knew that some of these children had died.

“It is just an awful, awful awful tragedy.”

Dr Pettigrew also told the inquiry there was no specific policy of informing parents about the risk associated with blood products such as factor concentrates when it emerged in 1983 and 1984 that there may be a link between such products and Aids, although they would have discussed the issues with them if they were asked.

Ms Richards asked: “Do you accept that as a matter of principle that the parents of boys at Yorkhill had a right to know that factor concentrates might infect their children with a fatal disease for which there was no treatment?”

Dr Pettigrew said it was a time of confusion and evolving evidence but they “could have done it better”.

She said: “When it was apparent that that was the case it would have been better if they had been informed and perhaps if there had been policy not only in our unit but in all units to inform parents of this.”

Dr Pettigrew told the inquiry she could remember one incident at the time, though she did not specify where it occurred, when a carer became infected with the virus from a patient and that parents were given advice on how to prevent transmission of viruses.

She said patients with HIV “felt quite stigmatised” and recalled how hospital porters at the time had announced, before any Yorkhill patients were found to be positive, that they would not transport a patient in a wheelchair or trolley if they were known to have Aids.

Thousands of patients across the UK were infected with HIV and hepatitis C – which was previously known as non-A, non-B hepatitis – through contaminated blood products in the 1970s and 1980s.

About 2,400 people died in what has been labelled the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS.

Earlier on Monday, the inquiry heard children with severe haemophilia on a home treatment programme were treated with commercial blood products because it was thought the supply was more reliable.

The inquiry heard the programme was introduced by Dr Michael Willoughby, who was in charge of haemophilia patients at the RHSC in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

It was said this made it possible for children to be treated for bleeds at home, particularly if they lived far from the hospital.

Ms Richards asked Dr Pettigrew whether she had any discussions with Dr Willoughby about why he chose to use commercial products rather than NHS products for the home therapy programme.

She replied: “He said when he was starting home therapy the Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service (SNBTS) could not supply sufficient or reliable amounts for him to use for his home therapy programme.”

Dr Pettigrew said she was not involved in any decisions around procurement.

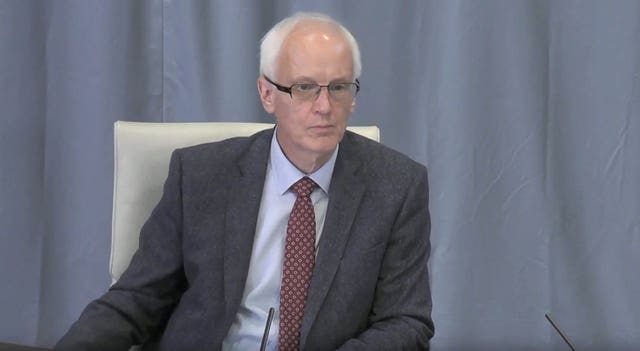

The UK-wide inquiry, taking place before chairman Sir Brian Langstaff, continues.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here